As parents, few moments strike more terror than witnessing a child choke or realizing they have swallowed a foreign object. The primal fear that grips you is paralyzing, a cold dread that time is both your greatest enemy and only ally. In these critical moments, knowledge is not just power—it is salvation. The first five minutes after such an incident are universally acknowledged by medical professionals as the "golden window," a brief period where calm, decisive action can literally mean the difference between a scary story told at family gatherings and an irreversible tragedy. This isn't about medical degrees; it's about empowered parenting. It's about transforming panic into procedure.

The initial shock is often the most dangerous part of the entire ordeal. A child's distress is a siren call to every parental instinct, which often screams to panic, to shake the child, to slap their back wildly, or to blindly reach fingers down their throat. These well-intentioned but misguided reactions can be catastrophically counterproductive, potentially pushing an object deeper into the airway or causing further injury to the delicate throat tissues. The first and most crucial step is not a physical maneuver, but a mental one: you must force yourself to be calm.

Your child is looking to you, their entire world, for cues. Your controlled breathing and clear voice can be their anchor in the storm of their own fear. Take one deep, deliberate breath. This single act centers you, floods your brain with oxygen, and allows the rational part of your mind to engage. Assess the situation with a swift, clinical eye. Is the child coughing forcefully? This is a good sign—it indicates a partially blocked airway and their body's own powerful reflex to clear it. Encourage this! Do not interfere. Is the cough weak, silent, or non-existent? Are they unable to cry or speak? Is their skin, particularly around the lips, beginning to take on a bluish tint? These are the cardinal signs of a complete airway obstruction, and this is when the clock starts ticking with a terrifying finality.

For a conscious infant under one year of age, the protocol is precise and must be followed meticulously. Position the baby face-down along your forearm, their head lower than their chest, and firmly support their jaw and head with your hand. Be careful not to cover their mouth or compress their soft throat. Rest this forearm on your thigh for added stability. With the heel of your other hand, deliver up to five firm back blows between the infant's shoulder blades. The force should be sharp and intended to dislodge, not to harm.

After each blow, check to see if the object has been ejected. If after five blows the airway remains blocked, carefully turn the infant over onto their back, keeping their head lower than their body. Using two fingers placed on the center of the breastbone, just below the nipple line, perform up to five quick chest thrusts, pushing inwards and downwards about 1.5 inches. The rhythm is not unlike a very forceful CPR compression, but the intent is to create an artificial cough by forcing air from the lungs. Continue cycling between five back blows and five chest thrusts until the object is dislodged, the infant begins to cry or breathe effectively, or they lose consciousness. The transition between these maneuvers must be smooth and swift; hesitation is a luxury you cannot afford.

For a conscious child over one year old or an adult, the universally recognized Heimlich maneuver, or abdominal thrusts, becomes the primary technique. Stand or kneel behind the child, wrapping your arms around their waist. Make a fist with one hand and place the thumb side against the middle of the child's abdomen, well above the navel but crucially below the bottom of the breastbone.

Never place your hands on the ribcage itself. Grasp your fist with your other hand and perform quick, upward thrusts into the abdomen. Each thrust should be a separate, distinct attempt to dislodge the object by forcing the diaphragm upward to expel air from the lungs. The motion is inward and upward, as if you are trying to lift the child off their feet. Continue with these thrusts until the object is expelled or the child becomes unconscious. It is vital to understand that the force required for a small three-year-old is vastly different from that for a sturdy ten-year-old. You must calibrate your strength to the size of the child to avoid causing internal injuries like bruised organs or, in extremely rare cases, a ruptured spleen.

The nightmare scenario is when efforts fail and the child loses consciousness. This is a heart-stopping turn of events, but it does not mean the end of the fight. Gently lower the child to a firm, flat surface on their back. Immediately shout for someone to call emergency services if you haven't already, but do not leave the child to make the call yourself unless you are utterly alone. Now, you transition from clearing an obstruction to performing CPR modified for a choked victim. Open the airway by tilting the head and lifting the chin.

Look inside the mouth. If you can see the object clearly and it is easily accessible, use a finger to sweep it out. Never perform a blind finger sweep, as you risk pushing the object further down. If you see nothing, or cannot safely remove it, begin CPR. For a child, give 30 chest compressions at a rate of 100-120 per minute, followed by two rescue breaths. Before each breath, open the mouth and look again for the object. The cycle of compressions and breaths may itself act to dislodge the item. Continue this cycle until help arrives or the child regains consciousness and begins breathing normally. The mental fortitude required to perform CPR on your own child is unimaginable, but it is this very action that sustains oxygenated blood flow to their brain, preserving life until professional medical teams can take over.

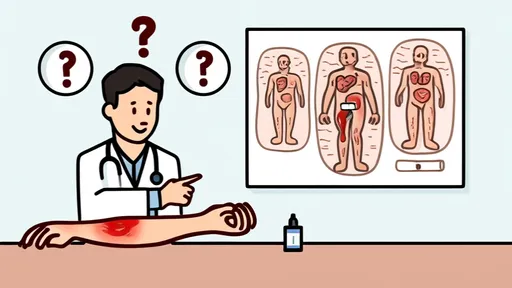

Once the immediate crisis has passed and the child is breathing, or once emergency medical services have arrived and assumed control, the emotional and psychological aftermath begins. Even if the object was successfully expelled and the child seems perfectly fine, a visit to the emergency room is non-negotiable. The physical trauma from the object itself or from the first aid maneuvers can cause internal swelling, bruising, or subtle injuries that are not immediately apparent.

A doctor needs to perform a thorough examination, which may include X-rays, especially if the object was a battery, magnet, or sharp item, to ensure nothing remains and no damage has been done. Furthermore, the psychological impact on both the child and the parent can be profound. The child may develop a fear of eating certain foods or experience nightmares. Parents are often wracked with guilt and replay the event in their minds endlessly. This is a normal reaction to an abnormal, traumatic event. Talking about it openly as a family, and seeking professional counseling if anxiety persists, is not a sign of weakness but a step towards healing.

The true power, however, lies not in reaction, but in prevention. The golden five minutes are precious, but they are a last line of defense. The first and best defense is a vigilant, proactive environment. Get down on your hands and knees and see the world from your child's perspective. What shiny, small, intriguing objects are within reach? Common household killers include button batteries, which can cause catastrophic chemical burns in just two hours; small magnets that can pinch together through intestinal walls if swallowed; coins; small toy parts; jewelry; and seemingly harmless foods like whole grapes, hot dog rounds, nuts, and hard candies. Food should be cut into appropriate sizes, and children should be taught to eat sitting down, not while running or playing. Toys should be age-graded for a reason—heed those warnings. This constant, mindful curation of their environment is the quiet, uncelebrated work of parenting that truly saves lives, ensuring the golden five minutes are a protocol you know in your bones but pray you never have to use.

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025