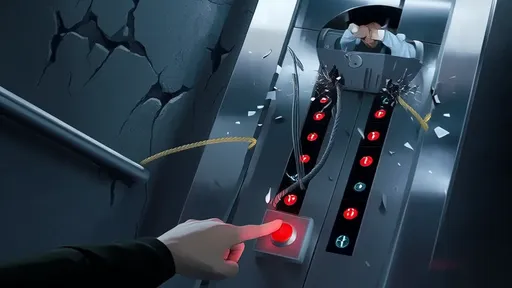

It’s a scenario that has likely crossed the mind of anyone who has ever stepped into an elevator: what if it suddenly drops? The stomach-lurching thought of a free-falling elevator car is the stuff of nightmares, and it has spawned a widely circulated piece of advice that feels both intuitive and action-oriented. The myth goes like this: if your elevator begins to plummet, you can save yourself by frantically pressing every single floor button on the panel. The logic, as the story suggests, is that this will somehow engage the safety systems or "catch" the elevator on one of the floors, bringing it to a halt. It’s a compelling idea, offering a sense of control in a terrifying, uncontrollable situation. But how much of this is based on the actual engineering and safety mechanisms of a modern elevator?

The truth is, this pervasive survival tip is a complete myth, and acting on it in a real emergency would be, at best, a useless distraction and, at worst, could prevent you from taking actions that might actually improve your safety. To understand why, we need to delve into how elevators are actually built and the sophisticated safety systems that have been standard for over a century.

Modern elevators are not simply boxes hanging from a rope that can snap. They are incredibly complex machines with multiple, redundant safety systems designed specifically to prevent a catastrophic free fall. The most important of these is the speed governor system. This mechanism consists of a governor pulley and a cable that runs the length of the elevator shaft, connected to the top of the car. If the elevator begins to descend at a speed that exceeds its rated limit—typically 25% faster than its normal operating speed—the governor triggers a mechanism that engages the car’s safeties.

These safeties, often called brakes or wedges, are installed on the underside of the elevator car. When activated, they physically clamp onto the guiderails that run vertically along the shaft. They do not slow the car down; they lock onto the rails with immense force, bringing the elevator to an abrupt and complete stop. This system is entirely mechanical and does not rely on electricity, motors, or any kind of electronic signal. It is a fail-safe designed to work even in a total power failure. The idea that pressing buttons could influence this purely mechanical process is therefore fundamentally flawed.

So, where does the button-pressing myth come from? Its origins are murky, but it likely stems from a misunderstanding of how elevator control systems work. In very old, relay-based systems, there was a concept of a "priority" or "attendant" mode where the car would bypass other calls to go directly to a specific floor. Some have speculated that hitting all buttons might confuse an old system into stopping, but this was never a designed safety feature. Modern elevators are controlled by sophisticated computer systems. Pressing a series of buttons simply sends electronic signals to the control board, registering those floors as destinations. In a emergency descent, this computer is likely already malfunctioning or overwhelmed, and adding more commands would do nothing to engage the physical safety brakes, which operate on a completely separate system.

In fact, the act of pressing all the buttons could have a minor negative effect. On some systems, the elevator is programmed to respond to calls in a specific order to optimize travel. Flooding the system with every single destination could, in theory, cause a slight delay in processing or create confusion in its routing logic, though this would be insignificant compared to the major mechanical event of a safeties engagement. A more practical downside is the waste of precious seconds and mental focus. In a crisis, your attention is your most valuable resource. Spending it on a futile, superstitious action means you are not focusing on actions that could genuinely help.

If pressing buttons won't save you, what should you do in the extremely unlikely event of an elevator failure? Safety experts universally agree on a set of actions. First and foremost, stay calm. Panic is your enemy. Next, press the alarm button and use the emergency phone or call button to alert building security or maintenance. This is the single most important thing you can do to get help on the way. If you have cell service, call 911 or the local emergency number directly.

Your next priority is to protect yourself in case the car does jerk to a stop, which is the most likely outcome thanks to the safeties. Brace yourself against a wall of the elevator to avoid being knocked off your feet. If there is a handrail, hold onto it tightly. The widely recommended position is to lie flat on your back on the floor of the elevator, spreading your weight evenly. However, this is often impractical in a crowded car. A more feasible alternative is to crouch down low, leaning against the wall, and cover your head with your arms to protect against falling debris, though the ceiling panels are designed to be lightweight for this very reason.

It is absolutely critical to know what not to do. Do not, under any circumstances, try to pry the doors open or attempt to climb out of the car. An elevator car can stop between floors, and the space between the car and the shaft wall is extremely dangerous. A sudden movement of the car could be fatal. The only time you should ever exit an elevator car is when it is stopped and level with a floor, and the doors are fully open. Your safest place is inside the reinforced cab until professional rescuers arrive.

The fear of elevator free-fall is deeply ingrained in our collective psyche, but it is important to contextualize the actual risk. True, unrestricted free-fall incidents are astonishingly rare. Elevators are statistically one of the safest modes of transportation. The numerous safety redundancies—overspeed governors, multiple braking systems, and buffer springs or pistons at the bottom of the shaft to absorb impact—make a deadly plunge a virtual impossibility in a properly maintained system. Most "falling" sensations are actually just the normal, brief deceleration when stopping at a floor or a minor misleveling issue.

Ultimately, the myth of pressing all the buttons is a classic example of a "just-so story" that provides a simple answer to a complex fear. It feels proactive, but it is based on a complete fiction. Real elevator safety lies not in superstitious rituals, but in understanding the robust engineering that protects you every day and knowing the correct, calm, and effective actions to take should the incredibly rare emergency occur. Trust the brakes, not the buttons.

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025