As a dog owner, few things are more concerning than watching your beloved companion struggle with mobility. For owners of large and giant breed dogs, the specter of hip dysplasia looms particularly large. This developmental disorder, where the ball and socket of the hip joint do not fit together properly, can lead to a lifetime of pain, arthritis, and limited mobility. However, the narrative surrounding this condition is shifting from one of management to one of proactive prevention. The cornerstone of this new approach is early intervention—a series of strategic actions taken during the critical growth phases of a puppy's life to significantly reduce the risk and severity of this debilitating condition.

The journey of a large breed puppy from a clumsy, oversized furball to a majestic adult is a rapid and metabolically intense process. Their skeletons are engineering marvels, but they are also vulnerable. Hip dysplasia is not a simple disease with a single cause; it is a complex, polygenic condition influenced by a combination of genetic predisposition and environmental factors. While we cannot yet edit a dog's genetic code to remove the risk, the environmental triggers are almost entirely within our control. This is where the power of early intervention truly lies. It is about creating the optimal conditions for a skeleton to build itself correctly, thereby mitigating the expression of any underlying genetic tendencies.

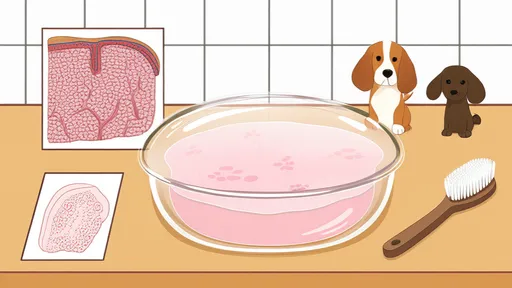

Perhaps the most critical, and most frequently mismanaged, factor is nutrition. The old adage of "feeding for a healthy, shiny coat" has been dangerously misinterpreted by many well-intentioned owners of large-breed puppies. The instinct to feed them more, to help them grow big and strong, is precisely the wrong approach. Rapid growth, spurred by excessive calorie intake and high levels of calcium, forces the bones to lengthen at a rate that the supporting muscles and tissues cannot match. This creates instability in the immature joint. The resulting laxity, or looseness, is a primary driver of dysplasia. The femoral head does not sit snugly in the acetabulum, and with every step, it grinds and damages the cartilage, setting the stage for premature arthritis.

The solution is not to underfeed, but to feed strategically. Reputable brands formulate specific large-breed puppy foods that are precisely calibrated for controlled growth. These diets are lower in calories and fat and have a carefully balanced calcium-to-phosphorus ratio. The goal is not to stunt growth, but to allow the puppy to reach its full genetic potential size at a steady, appropriate pace. This gives the musculoskeletal system the time it needs to develop in synchrony. The body condition score is a far better guide than the amount of food in the bowl; a puppy should be lean, with a visible waist and easily palpable ribs, not roly-poly.

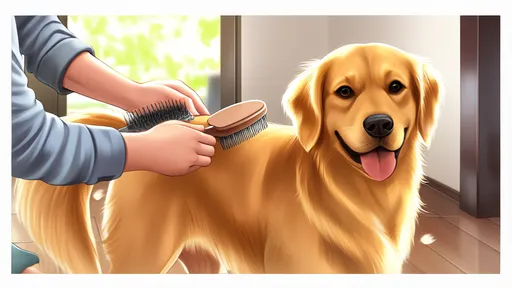

Closely tied to nutrition is the subject of exercise. The developing joints of a large-breed puppy are not designed for the high-impact, repetitive stress that many popular activities entail. Forced running on hard surfaces like concrete or asphalt, long-distance jogging with an owner, frantic games of fetch that involve sharp turns and sudden stops, and navigating steep flights of stairs are all activities that place immense strain on the hip joints. This repetitive trauma can exacerbate joint laxity and cause micro-injuries to the soft cartilage.

This does not mean condemning a puppy to a life of confinement. Exercise is vital for building the strong muscles that act as natural shock absorbers and stabilizers for the joints. The key is the type and surface of the activity. Controlled, self-paced exercise on soft, forgiving ground is ideal. Short, leisurely walks on grass or dirt, gentle play with a well-matched canine friend, and supervised swimming (an excellent non-weight-bearing exercise) are all fantastic choices. The mantra should be "little and often," rather than long periods of intense activity followed by prolonged rest. Allowing the puppy to set the pace and rest when tired is crucial.

Beyond diet and exercise, the early living environment plays a subtle but important role. Puppies raised on slippery surfaces like tile, laminate, or hardwood floors are constantly struggling for traction. Their legs splay outward with every step, placing abnormal stress on the hip joints and supporting ligaments. Providing ample traction through rubber-backed rugs, yoga mats, or even booties can make a significant difference in promoting a normal, stable gait during these formative months. Similarly, providing an orthopedic bed supports their joints during the long hours they spend sleeping and growing.

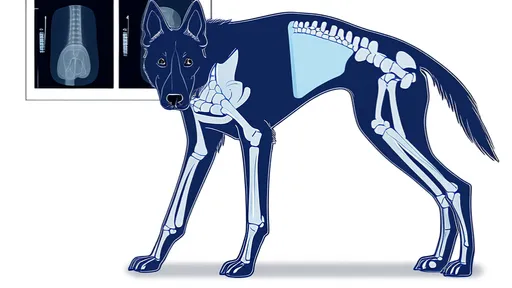

The role of the veterinarian is paramount in any early intervention strategy. This begins with the very first puppy check-up. A knowledgeable vet will discuss breed-specific risks with the owner and outline a proactive plan. While a definitive diagnosis of hip dysplasia often relies on radiographs (X-rays) taken once the dog is skeletally mature, usually around two years of age, there are earlier assessment tools. The Ortolani test is a manual manipulation performed under sedation that can detect palpable joint laxity in puppies as young as four months old. While not a diagnosis, a positive Ortolani sign is a powerful early warning indicator, allowing for an immediate intensification of preventive measures.

For puppies identified as high-risk, or for those showing early signs of discomfort, a range of supportive interventions can be introduced. Physical therapy techniques, including targeted exercises to strengthen the gluteal and quadriceps muscles, can dramatically improve joint stability. Weight management must be a relentless focus, as every extra pound translates directly to increased force on the hips. Some veterinarians may also recommend nutraceutical supplements like glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate, omega-3 fatty acids (EPA/DHA), and methylsulfonylmethane (MSM) to support joint health and reduce inflammation from the inside out, even before overt symptoms appear.

The old model of veterinary care was to wait and see, only acting when a dog began to visibly limp or show pain. That paradigm is obsolete. Today, the most successful outcomes are achieved by those who never see the symptoms at all. Early intervention for hip dysplasia is a testament to the power of preventive medicine. It is a commitment from the moment a puppy enters a home—a commitment to informed feeding, mindful exercise, and a partnership with a proactive veterinarian. It is a comprehensive strategy that acknowledges the vulnerability of rapid growth and seeks to guide it with wisdom and care. For the generations of large-breed dogs to come, this proactive approach promises a future with more running, more playing, and far less pain—a future built, quite literally, from the ground up.

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025